Indonesia Comes to Old City, Courtesy of Laura Cohn

Ed Hewitt, Art Matters

In the cracked-mirror Zeitgeist of the late 20th century, attaining a modicum of artistic and personal integration can take on the contours of a quest. For batik painter Laura F. Cohn, it took as much as migrating halfway around the world to Indonesia every six months. Cohn has spent half of every year since 1988 in the island republic, and the other half in her native Maine and new home in Narberth, PA, splitting her time living on opposite sides of the planet. This month, she will present a show of new batik work entitled “Indonesia in Olde City” at the Jasuta gallery, 122 Arch Street, Philadelphia. An opening reception will be held on Nov. 2, 5-9 p.m. The show will continue through Nov. 16.

Drawn by tales of life integrating seamlessly with art among the Hindu peoples of Indonesia, Cohn visited Bali as a traveler in 1988. Upon her return a few weeks after, she and everyone around her knew she would return to the islands.

“The arts are part of Hindu religious ritual, and there is a Hindu ritual in which worshippers take care to make offerings of food to the bad spirits as well as the good spirits, as all spirits have to be fed,” she said. “The care with which these rice offerings were placed on a little palm-leaf and placed on the ground was very graceful and very beautiful. Our own religious rituals tend to be rote and without any intrinsic value or beauty.”

In the careful, if ascetic rituals of the Balinese, Cohn found a certain completeness.

“The use of arts in rituals charges it much more, and its normalcy in their daily lives gives it power,” the eloquent 31-year-old said. “The woman who makes the masks is also a dancer and works in an office in town.”

Cohn returned to Indonesia in December 1988 and has spent at least half of each year there since, working both as a painter and with non-profit agencies promoting tourism and public and community arts projects. She worked with the Balinese batik master, “Jon” Viktor Sarjono, finding that life in Indonesia created a freedom that is difficult in the more advanced, moneyed climate of the United States.

“I had the liberty of producing work without the concept of scarcity,” she said. “It’s very liberating and empowering, and allows you to be more free in your decisions and work.”

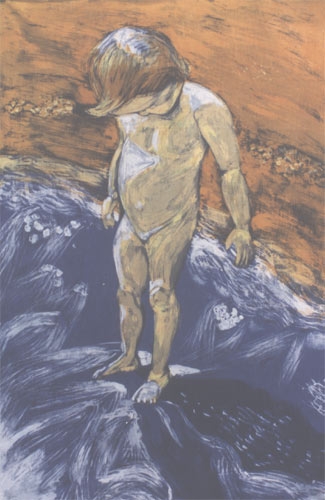

Cohn’s batik pieces manage a synthesis of painterly Western impressionistic techniques with the arduous and sometimes unpredictable batik process of first applying paint, then adding a preservative coat of wax before painting again. Cohn’s vivid and broad palette captures both the Impressionistic emphasis on light and color and the tenor, pace and palette of the Balinese milieu.

In the batiking process, a wax resist is applied to the cloth, which is then dipped in colored dye. After the dye is allowed to dry, the wax is stripped away and applied to the dried dye and other areas that the artist does not wish to absorb the dye. The process is repeated several times, once for each color in the painting. In Indonesia, where, despite the often near 100 percent humidity, high temperatures make for very rapid drying times. Cohn is able to work at a high rate of speed without the sometimes significant drying time that often limits the batik palette.

“People who know batik are often surprised that I can use 40 colors in a painting,” she said. “But in Indonesia, you don’t need to wait for days for a painting to dry before you can return to add new colors.”

Still, as the solar activated dyes dry, the colors often change dramatically, adding an element of uncertainty to the process. Cohn revels in this element and the spontaneity and surprise it generates.

“As a Westerner, I had always learned to believe that knowledge led to mastery,” she said. “But I believe in the power of play and the importance of giving up knowledge. I always teach that, but I had to trick myself, to begin work in a new medium that would force me to go back to the beginning, to revel in the intrinsic value of risk.”

“I was very comfortable in my painting medium, and with batik painting I had to give up complete control,” she remembered. “There is a tension and energy in anticipation and that element of the process has become an important metaphor in my own life.”

Cohn has decided to give up her ex-pat days and live in the United States, with occasional returns to the islands of her inspiration. Here in the land of electronic speed and automatic painting, Cohn will rather need to slow down her painting habits in deference to the longer drying periods created by the very different weather of the northeastern United States.

Now, when she returns to the studio to paint in the United States, she will need to relearn her art as, along with longer drying times, available (and legal) chemicals and dyes behave quite differently.

“In America, other people are working faster, and I’m going to have to learn to work slower,” she laughed.

Cohn encourages viewers to walk around the paintings to partake in the play of light through the cotton cloth and the often dramatic shifts of hue that occur when the batik dyes are not filtered by wax. The back of a painting is not treated with wax, and the dyes soak through unchanged. Cohn finds a sociological metaphor in the effect, and rather than hanging against walls, the 50 paintings in this show will hang free in space, with backlit effects resembling stained glass windows.

The scrolling frames for the paintings in this show were built and hand-carved by Indonesian woodworkers. Like most of Cohn’s shows, this exhibition of 50 paintings will include native Indonesian crafts, music and incense, and educational presentations on video and by Cohn herself. “I’ll be hitting as many sense as possible,” she said. Cohn, who typically puts on her own shows, said that this time out she is enjoying the collaborative nature of her relationships with gallery owner Jenny Jasuta.

Cohn is active as an arts educator, from imparting management and marketing skills to art students to giving lectures on Balinese culture, art and even tourism. She plans to spend two months each year in Indonesia “in a painting frenzy,” keeping in touch with her friends and pouring the fruits of her success back into the local economies. The people of Indonesia are rarely far from her thoughts, and she wonders about the day that she no longer considers herself an “Indonesian artist.” For now, she will continue her cross cultural outreach.

“Simply because I believe in Indonesia,” she said.